CEO of WeWork Adam Neumann

Getty Images

WeWork's parent company, the We Company, made a splash earlier this week with the release of its much-anticipated IPO prospectus.

The company's S-1 lays the groundwork for what is widely expected to be one of the largest initial public offerings of the year, second only to Uber's IPO in May.

It's also filled with unusual items that should scare off all but the hardiest investors with a healthy appetite for risk. Here's a rundown.

Mounting losses

WeWork's revenue for the first half of 2019 may have been more than double that of a year earlier, but its losses are accelerating just as rapidly. The company indicated in its IPO filing that losses ballooned to more than $900 million in the first six months of the year, which follows full-year net losses of $1.9 billion in 2018.

Massive losses have become part and parcel of unicorn IPOs, as demonstrated by the debut of fellow high-flying tech companies Uber and Lyft earlier this year, among many others. But WeWork continues to face tough questions around the sustainability of its business and few of them were answered in its S-1.

"You can say I'm growing faster, but you can't say that if for every dollar you're getting, you're losing a dollar," said Renaissance Capital principal Kathleen Smith.

Similarly, MKM Partners' Rohit Kulkarni said in a note Friday that investors would "have to take a big leap of faith in order to believe that WeWork would show signs of a sustainable economic model" given the rising costs across its 528 locations. He said WeWork could soon find itself strapped for cash.

"At an estimated $1500-200mn in cash burn per month, we believe the company has about six months in execution runway ahead before facing a cash crunch," Kulkarni wrote in a research note.

Expensive lease agreements

WeWork's lease obligations bear some attention.

The company signs long-term leases with landlords that last up to 15 years, which requires it to pay hundreds of millions of dollars in future rent, according to data provider CB Insights. In the S-1 filing, WeWork said future lease payment obligations were $47.2 billion as of June 30, up from roughly $34 billion at the end of 2018.

At the same time, WeWork offers short-term rental contracts to members, in an effort to provide flexibility, collecting rent at an average of a two-year timeframe, Smith said.

This is a boon for its members, but could present a risk to WeWork's business, as these short-term renters could up and leave at any time, leaving the company on the hook for long-term rentals.

"That mismatch can be deadly in a recession," Smith said. "It means the company has got to be able to pay the lease costs. If for some reason there's price pressure, lack of renewals, cancellations and they have a time where they're not leasing out their space, that could be a very huge risk in a recession."

The company's declining revenue per membership also raises some concerns.

WeWork estimates a total addressable market opportunity of $945 billion, when applying its average revenue per WeWork membership to its potential member population, the filing states. However, WeWork also warned that revenues per member will decline in the future as it expands internationally into "lower-priced markets."

"Investors want to see [average revenue per member] increase, because that can prove this idea of ancillary services," Smith said.

Services are expected to be a long-term driver of the company's revenue. CEO Adam Neumann has stated previously that he sees WeWork as a "global platform" for things like "space-as-a-service," a play on the phrase software-as-a-service.

If WeWork is already having trouble increasing its average revenue per member, it could be challenging to get members to shell out a couple extra dollars on things like software or other services.

Puzzling corporate structure and unpredictable China business

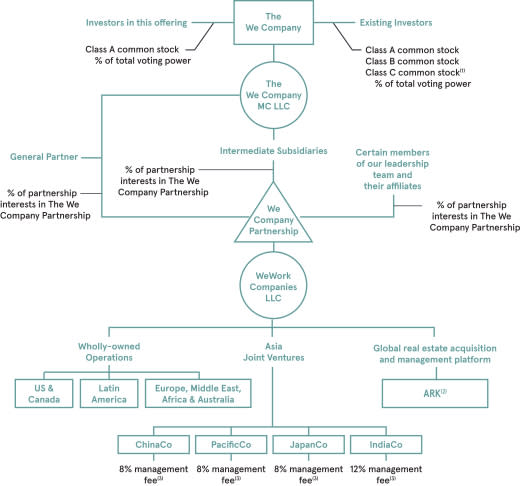

After WeWork rebranded to become The We Company in April, it adopted a complicated corporate structure, called an umbrella partnership corporation, or Up-C.

In effect, this turned WeWork into a limited liability company, with The We Company overseeing it and joint ventures in Asia, as well as other related entities, such as its fund ARK Capital Advisors, which oversees global real estate management and acquisitions. (The acronym stands for Adam, Rebekah and Kids, in reference to his wife -- who's listed as a co-founder and wields significant influence at the company -- and their five children.)

This chart from the S-1 shows how complicated it all is:

The Up-C structure has tax benefits for Neumann and other executives, as they'll be able to pay tax on any profits at an individual income-tax rate, according to the Financial Times. Meanwhile, public shareholders will be subject to double taxation, since the holding company will be taxed on income and investors will pay another tax on dividends.

In its S-1, WeWork said the Up-C structure would give it more flexibility to pursue acquisitions, while keeping debts and obligations of its other businesses separate.

"Such a structure allows us to separate our WeWork space-as-a-service offering from the rest of our existing businesses, and will also allow us to hold separately any future business areas into which we may expand," the filing states.

Kulkarni said in an interview with CNBC that WeWork's business in Asia is still in the early stages of development, so the structure allows them to "isolate the losses" associated with it.

In the company's S-1, WeWork noted that its contribution margin, which is the revenue left from membership and services after subtracting operating expenses of those locations, would have been three percentage points higher if it had excluded the China business.

WeWork faces unique risks with its operations in China. Business in the region is run by groups it can't control, local laws are different in terms of the length of leases and it falls under the 2017 China Cybersecurity Law, which gives the Chinese government access to enterprise data.

Kulkarni said he believes WeWork hasn't provided "sufficient disclosures around how the China and Asia assets are held" and that its confusing corporate structure could potentially present significant risks.

"It's a puzzle that needs to be solved," Kulkarni said.

An all-male board of directors

The We Company disclosed who will serve on its board of directors in its IPO prospectus. Not a single woman will serve on the company's seven-member board, which could potentially open it up to criticism later on down the line.

Neumann is chairman of the board and is joined by Bruce Dunlevie, a founding partner of Benchmark Capital, Ronald Fish, a vice chairman of WeWork's biggest backer, SoftBank. Lewis Frankfort, Steven Langman, Mark Schwartz and John Zhao also serve as directors.

By appointing solely male directors, WeWork is bucking the larger trend toward gender inclusive boards. As of last month, every S&P 500 company had at least one female director on its board. Having a more-diverse board is widely viewed as an avenue toward better shareholder returns.

CEO Adam Neumann's control and potential conflicts of interest

If you're betting on WeWork, you're betting on Neumann.

He controls the majority of the voting rights through the company's class B and C shares, with both classes carrying 20 votes per share compared to class A shares, which have one vote per share. Neumann's holdings could further increase as a result of a pre-IPO award option of up about 42.5 million shares, which will vest over the next 10 years.

Complicating things, WeWork leases and pays rent on buildings owned in part by Neumann. He has ownership stakes in four commercial properties leased to WeWork, the S-1 states. Between 2016 and June 2019, the company had paid $20.9 million to the landlords overseeing these leases, which in effect includes Neumann.

Additionally, when WeWork rebranded to become The We Company in April, it acquired the trademark to "We" from We Holdings LLC, an investment vehicle with Neumann and co-founder Miguel McKelvey. As part of the deal, We Holdings LLC got an additional stake in We worth $5.9 billion.

These kinds of transactions are things investors typically don't like to see, Smith said.

So much of the company is riding on Neumann that he was included among the risks listed in WeWork's S-1. The company noted that Neumann is "critical" to its operations, yet it has "no employment agreement in place."

"If Adam does not continue to serve as our Chief Executive Officer, it could have a material adverse effect on our business," the filing states.

Furthermore, should Neumann ever become permanently disabled or deceased, his wife Rebekah, who serves as the company's chief brand and impact officer, is one of two other people who will choose his successor. If two preselected directors are no longer serving on the board, Rebekah can also select which board members will assist her in the selection process.

WeWork acknowledges in the S-1 that Neumann has "deep involvement in all aspects of the growth" of the company, adding that he has "proven he can simultaneously wear the hats of visionary, operator and innovator, while thriving as a community and culture creator."

0 Comments